Lecture : 3 min

19 novembre 2024

TENDANCES EN MATIÈRE DE TECHNOLOGIES ET DE MALADIES

Point de vue d’expert

Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease: a Resurging Menace?

In recent months, the medical community has observed an alarming increase in cases of invasive Group A Streptococcus (iGAS) infection worldwide. This development has reignited concerns over the pathogenic potential of Group A Streptococcus (GAS) and its capacity to cause severe, often life-threatening diseases.

Invasive Group A Streptococcus

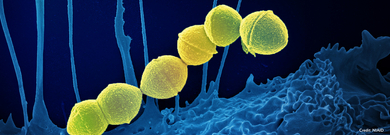

Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as GAS or Strep A, is a bacterium commonly found in the human throat and on the skin. It causes a spectrum of illnesses, most frequently mild infections like pharyngitis (strep throat), impetigo, and scarlet fever.1

Invasive infections occur when the bacteria penetrate a normally sterile site in the body, such as the bloodstream, muscles, or lungs, leading to life-threatening diseases like necrotizing fasciitis, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS), bacteremia, and post-immune mediated diseases, such as post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, acute rheumatic fever, and rheumatic heart disease.1,2

Historical Context

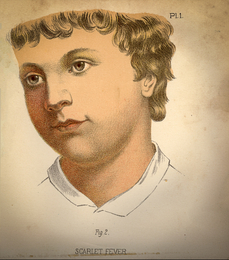

The pathogenicity of GAS has been recognized for centuries. However, it was not until the 19th century that the bacterium was identified and linked to specific diseases.2 Over the years, the incidence of GAS infections has fluctuated, with notable outbreaks in the early 20th century and a resurgence in the 1980s2. Advances in antibiotics and public health measures have generally kept GAS infections in check, but the recent spike in iGAS cases signals a critical need for renewed vigilance.

Scarlet fever, illustration from a "Warren's Household Physician" book of 1885.

Recent Reports of Invasive Group A Streptococcus Cases

Epidemiological data indicated a significant increase in iGAS cases across Europe, including France, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom in 2022.1 Children under 10 years of age were the group most affected in these outbreaks.

Australia experienced a similar post-pandemic increase3 and Canada saw over 4 600 cases of iGAS in 2023, a 40% increase over the previous yearly high.4

In the U.S., the Denver metropolitan area of Colorado and the entire state of Minnesota observed a resurgence of iGAS during the fall of 2022, especially among children and adolescents5 and more than a dozen children were diagnosed with iGAS infections at a children's hospital in South Carolina in the first 5 months of 2023.6

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that rates of serious GAS disease have been increasing since 2014, but the number of serious GAS infections reached a 20-year high in 2023.7 According to the CDC, there have been between 20 000 to 27 000 cases of iGAS per year in the U.S. in the last 5 years, resulting in approximately 2 000 deaths each year.7

An ongoing outbreak in Japan has recorded 977 cases of STSS in the first half of 2024, surpassing 2023’s previous record of 941 preliminary infections.8 A record 77 deaths were reported in the first three months of 2024 due to iGAS STSS, approaching the 97 deaths caused by STSS last year which was the second-highest number of fatalities since 2019.8

What is causing the recent surges?

Resurgences in both iGAS and GAS pharyngitis have been observed toward the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.3,6,9 One hypothesis for this trend is a lack of exposure to GAS due to social distancing and other safety measures implemented during the pandemic, resulting in an unprepared immune system post-pandemic. This is especially true for school children under ten who may have experienced these impacts during critical years of immune development.

Changes in the bacteria themselves may also play a role. The emergence of a new variant of Strep A, the so-called M1UK variant, was first reported in 2019 and linked to a marked increase in invasive infections, seasonal scarlet fever surges, and expression of a superantigen toxin.10 This strain was linked to serious invasive cases in Australia, and its isolates have been detected in several countries,10 indicating that this more virulent form of Strep A could be driving an increase in severe GAS infections.

What is the connection between GAS and iGAS?

The link between GAS pharyngitis and iGAS is not well established. Indeed, it is a commonly held belief that iGAS results predominantly from skin colonization or infections, and rarely from pharyngeal sources, putting the utility of GAS pharyngitis testing as a means of limiting iGAS into question. This paradigm has been challenged, however, as the strains causing invasive infections are the most prevalent causes of GAS pharyngitis11 and high levels of transmission from throat to skin have been reported.12

Broad overlap between strains causing non-invasive infection in children and contemporary strains causing iGAS has been observed, and the same strains causing both iGAS and pharyngitis have been linked epidemiologically and clustered within the same outbreak.9,11

Finally, direct seeding of iGAS from pharyngeal infection is increasingly described, particularly in children. A recent study from the UK Health Security Agency investigated the rise in iGAS lower respiratory tract infections in the United Kingdom.13 This communication highlighted that misdiagnosis or late diagnosis of GAS pharyngitis can have mortal consequences. Of the 147 children who passed away from iGAS lower respiratory tract infections, 127 (86%) attended an emergency department, with 31% attending at least twice within 21 days after symptom onset. And yet, of 32 children with sample dates, 16 were not tested for GAS until or after the day they died.

What can healthcare professionals do to monitor and manage iGAS?

Invasive GAS infections are life-threatening infections that require early recognition, aggressive treatment and specific therapies for successful management.2 Enhanced surveillance and timely reporting are crucial for the early detection and control of iGAS outbreaks. Clinicians should vigilantly monitor for signs and symptoms of severe GAS infections, especially in high-risk populations: children and the elderly, immunocompromised people, and those with chronic diseases. They should also report case clusters to public health authorities promptly to facilitate outbreak investigations and implement control measures.7

Given its rapid clinical progression, effective management of iGAS infections hinges on early diagnosis of the disease and prompt initiation of supportive care (often intensive care) together with antibacterial therapy.2

Considering the epidemiological links between GAS and iGAS, it can be hypothesized that addressing GAS pharyngitis through early detection and intervention would lower the total GAS burden and, in turn, reduce the potential for invasive infections.

Conclusion

While iGAS is relatively rare, the recent spikes in infections warrant attention. Clinicians play a pivotal role in the early detection, treatment, and prevention of iGAS. By staying informed about current trends, employing rapid diagnostic techniques, and adhering to evidence-based management strategies, healthcare providers can mitigate the impact of this re-emerging threat.

- Increased incidence of scarlet fever and invasive Group A Streptococcus infection - multi-country. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON429

- Steer AC, Lamagni T, Curtis N, Carapetis JR. Invasive group a streptococcal disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Drugs. 2012;72(9):1213-1227. doi:10.2165/11634180-000000000-00000

- Abo Y-N, Oliver J, McMinn A, et al. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal disease among Australian children coinciding with northern hemisphere surges. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;41:100873. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100873

- Aggressive, often deadly form of strep hits record-high case numbers in Canada | CBC News. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ontario-strep-deaths-invasive-group-a-streptococcal-disease-1.7085755

- Barnes M, Youngkin E, Zipprich J, et al. Notes from the Field: Increase in Pediatric Invasive Group A Streptococcus Infections - Colorado and Minnesota, October-December 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(10):265-267. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7210a4

- “Unprecedented” uptick in invasive group A strep infections | MUSC | Charleston, SC. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://web.musc.edu/about/news-center/2023/05/16/unprecedented-uptick-in-invasive-group-a-strep-infections

- Group A Strep Disease Surveillance and Trends | Group A Strep | CDC. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/group-a-strep/php/surveillance/index.html

- STSS: Japan reports record spike in potentially deadly bacterial infection | CNN. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/2024/06/17/asia/japan-record-spike-stss-bacterial-infection-intl-hnk/index.html

- Vieira A, Wan Y, Ryan Y, et al. Rapid expansion and international spread of M1UK in the post-pandemic UK upsurge of Streptococcus pyogenes. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):3916. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-47929-7

- Davies MR, Keller N, Brouwer S, et al. Detection of Streptococcus pyogenes M1UK in Australia and characterization of the mutation driving enhanced expression of superantigen SpeA. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1051. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36717-4

- Li Y, Dominguez S, Nanduri SA, et al. Genomic Characterization of Group A Streptococci Causing Pharyngitis and Invasive Disease in Colorado, USA, June 2016- April 2017. J Infect Dis. 2022;225(10):1841-1851. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiab565

- Lacey JA, Marcato AJ, Chisholm RH, et al. Evaluating the role of asymptomatic throat carriage of Streptococcus pyogenes in impetigo transmission in remote Aboriginal communities in Northern Territory, Australia: a retrospective genomic analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2023;4(7):e524-e533. doi:10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00068-X

- Wrenn K, Blomquist PB, Inzoungou-Massanga C, et al. Surge of lower respiratory tract group A streptococcal infections in England in winter 2022: epidemiology and clinical profile. Lancet. 2023;402 Suppl 1:S93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02095-0

Lire la suite

PLUS