4m Read

19. marraskuuta 2024

TECH AND DISEASE TRENDS

Expert Perspective

Candida auris: Rising Threat and Future Implications

Candida auris as a Global Threat

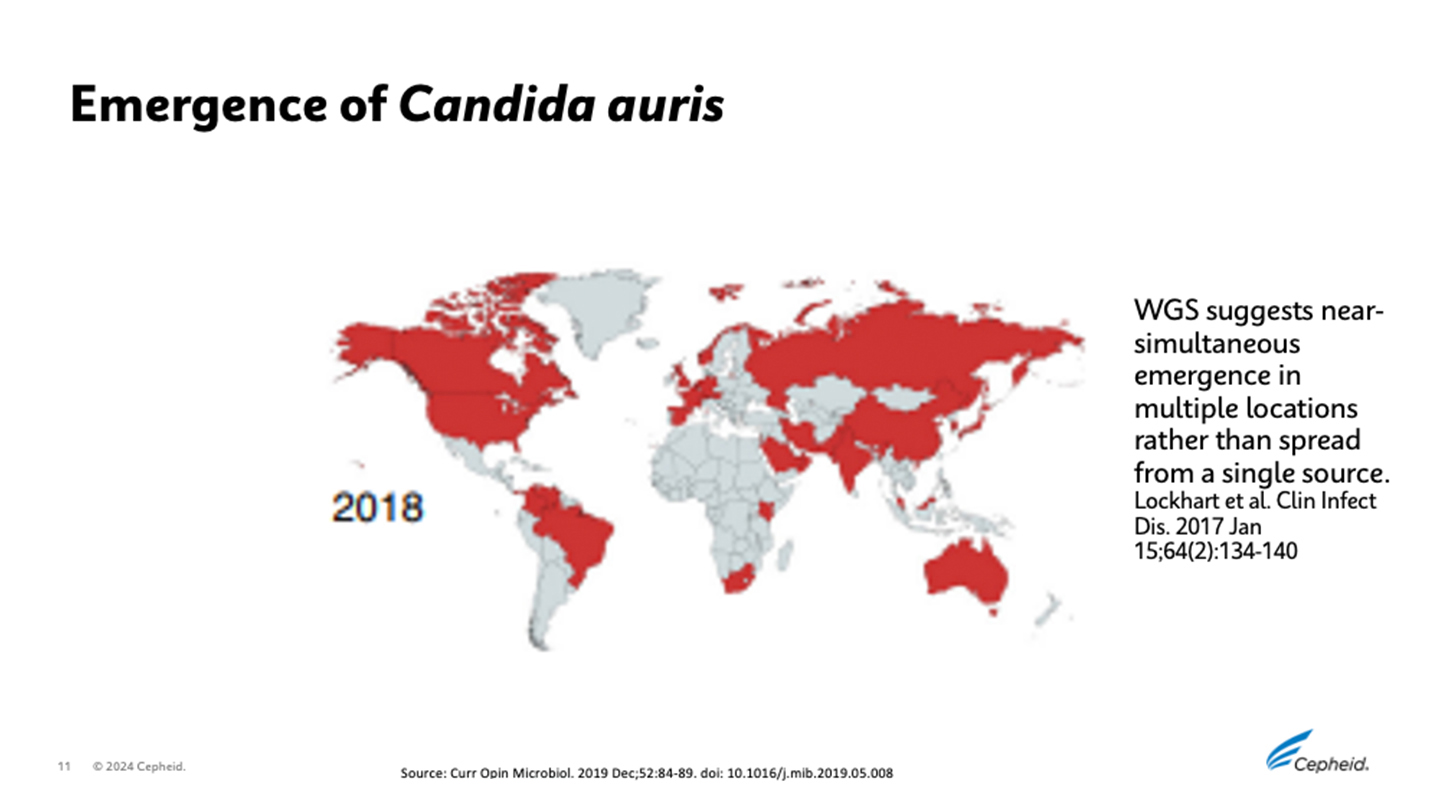

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has labeled Candida auris a “global threat,” deeming the threat level urgent.1 C. auris, a fungal pathogen, has emerged as a serious health concern due to its potential to cause invasive infections and increasing resistance to antifungal drugs. First discovered in 2009 in Japan,2 C. auris has rapidly gained attention as a potential cause of severe, life-threatening bloodstream infections and outbreaks in healthcare facilities such as hospitals and nursing homes.3

Clinical Significance of C. auris

C. auris colonizes the skin and nose of some hospitalized patients without causing disease.4 Colonization with C. auris can spread in healthcare facilities as it is transferred to surfaces on which it can persist for days to weeks.3 Colonization of a patient can persist for months, or even indefinitely,5 providing ample opportunity to spread.

C. auris is a particularly hardy fungus and resists decolonization and disinfection agents known to be effective against other Candida species.3 This makes outbreak management especially challenging.

Serious invasive diseases have been observed in 5-10% of colonized individuals.6 These infections have high mortality rates in fragile hospital and nursing home patients, ranging from 30% to 72%.3

Cases Increase During the COVID-19 Pandemic

C. auris has been identified across South Asia, East Asia, Africa, South America, and Iran. It has become widespread across all continents except Antarctica3 with increased cases observed during the COVID-19 pandemic.7

C. auris began spreading in the U.S. in 2015 and the number of reported cases increased 318% in 2018 compared to the average reported from 2015-2017.1 This has caused public health agencies, infection preventionists, researchers, and diagnostic providers to take notice.

One of the most concerning aspects of C. auris is its high level of resistance to antifungal medications. Treatment failures have been reported with certain antifungal drugs and pan-resistance to multiple drug classes has been observed.1, 3

In its 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report the CDC noted that its fungal experts had never received a report describing a Candida infection resistant to all antifungal medications, let alone Candida that spreads easily between patients.1

In response to the global threat, the CDC sounded the alarm in the U.S. and labeled C. auris as one of 5 urgent antimicrobial threats to society.1

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's approval of rezafungin in 2023 provides a promising new treatment option for C. auris infections8 but fast and accurate detection of the fungus is essential to managing this threat.

Image source: https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

Laboratory Detection and Identification

Screening patients for C. auris is a key preventative measure against outbreaks in healthcare facilities. However, accurate detection and identification of C. auris can be challenging.

Phenotypic identification systems can be inaccurate, leading to the misidentification of C. auris.9 Culturing the fungus requires specific biosafety conditions and takes days.

The CDC recommends mass spectrometry and molecular methods such as sequencing and PCR to detect and identify C. auris accurately. Isolates can also be sent to public health and reference laboratories for identification. While these mechanisms will provide accurate results, facilities may not have access to technologies such as mass spectrometry and sequencing. The turnaround time for sending samples out for testing can also cause delays during the critical window to detect colonization and prevent spread.

The Impact of In-House PCR Screening

Implementing in-house PCR testing to screen for C. auris has yielded positive results. It allows for earlier identification of colonized patients and potential cost savings related to isolation and testing.11 This approach can be more efficient than sending samples out for testing while providing reliable results.

The Road Ahead

As C. auris cases continue to rise and antimicrobial resistance becomes more prevalent, faster and more accurate testing solutions will be crucial tools for detecting cases early and helping prevent outbreaks.

Some commercial PCR-based tests that detect C. auris exist.9 However, current tests are designed to be run by trained professionals in laboratory environments.

Such testing might not be easily accessible in settings such as nursing homes, where patients most susceptible to severe C. auris infections may reside.

A prototype rapid, on-demand surveillance test for C. auris has been designed to provide accurate results in less than an hour in near-patient settings.10

The prototype test is designed to be run on Cepheid’s GeneXpert® system, which allows testing in laboratory settings and at the point of care. Such a test could lead to early detection and intervention in healthcare settings, potentially improving clinical, financial, and operational outcomes.

C. auris presents a significant challenge to healthcare systems worldwide due to its potential to cause invasive infections, high mortality rates, and resistance to antifungal drugs. Vigilance, staff education, evolving guidelines, continued drug and disinfecting method development, and innovative testing solutions are crucial to addressing this emerging threat.

Viitteet:

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, Georgia: National Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Infectious Diseases (U.S.); 2019 Nov.

2. Satoh K, Makimura K, Hasumi Y, Nishiyama Y, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol Immunol. 2009 Jan;53(1):41–4.

3. Sikora A, Hashmi MF, Zahra F. Candida auris. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

4. About C. auris [Internet]. CDC: Candida auris (C. auris). [cited 2024 Jun 2]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/candida-auris/about/index.html

5. Biswal M, Rudramurthy SM, Jain N, Shamanth AS, Sharma D, Jain K, et al. Controlling a possible outbreak of Candida auris infection: lessons learnt from multiple interventions. J Hosp Infect. 2017 Dec;97(4):363–70.

6. Sansom SE, Gussin GM, Schoeny M, Singh RD, Adil H, Bell P, et al. Rapid Environmental Contamination With Candida auris and Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Pathogens Near Colonized Patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 May 15;78(5):1276–84.

7. Pandak N, Al Sidairi H, Al-Zakwani I, Al Balushi Z, Chhetri S, Ba’Omar M, et al. The Outcome of Antibiotic Overuse before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Oman. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023 Nov 27;12(12).

8. Syed YY. Rezafungin: First Approval. Drugs. 2023 Jun;83(9):833–40.

9. Identification of C. auris | Candida auris (C. auris) | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 2]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/candida-auris/hcp/laboratories/identification-of-c-auris.html

10. Rossana Rosa, Adriana Jimenez, David Andrews, Huy Dinh, Katiuska Parra, Octavio Martinez, Lilian M Abbo, Impact of In-house Candida auris Polymerase Chain Reaction Screening on Admission on the Incidence Rates of Surveillance and Blood Cultures With C. auris and Associated Cost Savings, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Volume 10, Issue 11, November 2023, ofad567, https://doi.org/10:1093/ofid/ofad567

11. Banik S, Ozay B, Trejo M, Zhu Y, Kanna C, Santellan C, et al. A simple and sensitive test for Candida auris colonization, surveillance, and infection control suitable for near patient use. J Clin Microbiol. 2024 Jun 18;e0052524.

Read Next

LISÄÄ